Pros and Cons

What are the benefits and challenges of implementing democratic principles in the classroom?

Challenges

What are the barriers to implementing democratic principles within the classroom?

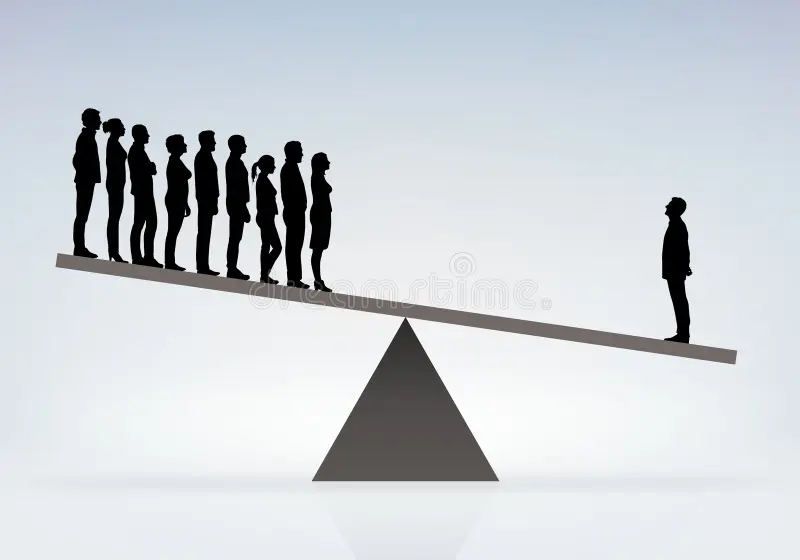

Power Imbalances

A significant challenge in democratic education is the need to address power imbalances. Systems of marginalization and oppression often unintentionally surface in classrooms, reinforcing broader social inequalities unless these dynamics are consciously disrupted (Graham, 2018). Traditional education often enforces strict hierarchies of power and control, which can limit student agency and perpetuate systemic inequities (Martin-Sanchez & Flores-Rodriguez, 2018; Raywid, 1987). Those in positions of social privilege continue to shape educational spaces, influencing students to adopt passive roles within structures that reflect and sustain existing power imbalances. When student voices and democratic engagement are not prioritized, teachers may struggle to establish genuine legitimacy, instead relying on authority alone, which can further marginalize learners. Martin-Sanchez and Flores-Rodriguez (2018) argue that in conventional curricula, students may not perceive teacher authority as valid, creating tension between imposed compliance and the pursuit of autonomy.

Curriculum and Testing

Another obstacle that democratic education must overcome is curriculum and testing. Teachers face pressure from standardized tests and rigid curricula that emphasize rote memorization, sidelining more engaging learning experiences. In Europe, there is widespread interest to design curricula that builds skills for effective interaction, democratic action, social responsibility, and critical thinking, but there is a significant lack of resources to help teachers evaluate these skills (Waatainen & Chu, 2024). Martin-Sanchez and Flores-Rodriguez (2018) offer similar critiques, noting that traditional education prioritizes curriculum over the emotional and critical development of students. Taken together, rigid curricula and standardized testing can hinder the flexibility and inclusivity needed for democratic education, potentially marginalizing student input and perpetuating inequalities.

Lack of Meaningful Student Participation

Often in schools, a lack of meaningful student participation undermines the principles of democracy and student empowerment. Teachers may not engage students in real-world activities and have described finding it challenging to capture genuine student perspectives, often struggling to get students to articulate their thoughts, sometimes leading to teachers simply giving them the answers (Waatainen & Chu, 2024). Some students may also express frustration with school rules and expectations that don't relate to meaningful learning or disrupt their engagement (Graham, 2018). This lack of meaningful participation can lead to disengaged students who do not subscribe to classroom norms, inhibiting the development of critical thinking and democratic values.

Time and Resource Constraints

Time and resource constraints can significantly impede the implementation of student-centered, engaging, and equitable learning experiences. Students often do not have enough time to fully explore complex ideas or conduct in-depth research because teachers are required to fit activities into already full schedules (Waatainen & Chu, 2024). The fast pace and intensity of designing lessons and collecting data in real classrooms mean that sometimes questions are left unasked, important materials uncollected, and learning undocumented. Overall, time and resource limitations can prevent teachers and students from fully engaging in the kinds of meaningful learning experiences that foster critical thinking, civic engagement, and democratic values. This ultimately undermines the goals of democratic education, which requires thoughtful deliberation, thorough investigation, and inclusive participation.

Benefits

What are the benefits of implementing democratic principles within the classroom?

Active Participation

Considering the advantages of democracy in classrooms, active participation emerges as a key strength. Giving students a chance to contribute to deliberations that mirror real-world decision-making processes allows educators to engage their students in meaningful and collaborative dialogue (Waatainen & Chu, 2024). This, in turn, equips them with the necessary age-appropriate tools and knowledge to navigate the political landscape and understand their role in society as current and future contributors.

Documentation is one way in which educators can provide these vital experiences for students. Falk and Darling-Hammond (2010) state “[t]eachers who [view documentation as a negotiated experience between learners and their environment] provide active learning opportunities, using what they learn from observing learners' actions and their work” (p. 74). In other words, recording student learning is necessary because it fosters engagement and ownership over their learning. When students see their ideas, questions, and progress documented and revisited, they develop a greater sense of agency, motivation, and confidence.

Respect for Human Rights

When weighing the advantages of democracy in classrooms, human rights is another notable benefit of its implementation. A core tenet of democratic learning involves confronting social injustices to ensure classrooms do not replicate broader societal issues, thereby upholding the human rights and dignity of all students. Graham (2018) suggests that responding to issues of inequity in education requires a coordinated approach, where democracy and teacher authority—which he importantly distinguishes from teacher power—work simultaneously to achieve the best interests for students. He states, “[w]hen teachers cultivate student voice and craft a shared vision, teacher authority can support, rather than undermining, democracy and social justice” (Graham, 2018, p. 511). Ultimately, by balancing authority with democratic participation, educators can create spaces that challenge systemic inequalities rather than reinforce them.

Critical Capacity

Another central benefit of incorporating democratic principles into education is a focus on developing critical thinking skills, which is essential for enabling young students to thoughtfully engage with the world around them. However, Martin-Sanchez and Flores-Rodriguez (2018) echo Chomsky’s assertion that contemporary education systems tend to disempower both teachers and students in an effort to streamline education. It is thus necessary to break this inclination, if the goal is to achieve a truly democratic education system.

According to Martin-Sanchez and Flores-Rodriguez (2018), this begins in teacher education programs; they state, “[k]nowledge and social responsibility must be introduced into future teacher training. It must be training which educates and enlightens teachers, turning them into critical individuals capable of transmitting that same critical capacity to their students” (p. 73). Giving prospective teachers the necessary tools and opportunities to develop their own critical awareness not only allows them to model that to their students, but also enables them to engage the broader learning community in critical discourse. As Falk and Darling-Hammond (2010) succinctly put it, “samples of students' work, exhibitions, performances, and other evidence collected by teachers give parents/caregivers, and the public at large, educative information about individual and group learning” (p. 78). By fostering critical capacity in teachers, education systems can create a ripple effect, empowering students and the wider community to engage in meaningful, informed dialogue that strengthens democratic participation.

School as a Site of Social Justice and Emancipation

A core advantage of incorporating democracy into education lies in its potential to serve as a social and emancipatory alternative. According to Martin-Sanchez and Flores-Rodriguez (2018), public schools must serve as a social and liberatory force that challenges power structures rooted in racial and class-based discrimination while simultaneously working to dismantle historical inequalities. As previously mentioned this implicates everyone in the learning community, requiring them to work collaboratively to develop critical awareness and advocating for structural change. As we have briefly touched on prior and will elaborate on in our ‘putting it into practice’ section, there are numerous ways in which education systems can achieve this type of systemic transformation.

Commitment

Student commitment is another significant advantage of incorporating democratic practices in education. The active participation and sense of ownership fostered by democratic approaches can lead to increased commitment, interest, and engagement. Martin-Sanchez and Flores-Rodriguez (2018) maintain that education should “ensure the active and participative inclusion of each person in social life” (p. 55). One way of achieving this, Falk and Darling-Hammond (2010) highlight, is documenting student learning in order to bring students’ familial, cultural, and personal knowledge into the spotlight, fostering deeper connections to the educational process and a heightened sense of connection for students in the classroom. Raywid (1987) notes that “democratic practice affords the most humane treatment possible for people of almost any age” (p. 480), suggesting a commitment to the well-being and development of all learners. By valuing the characteristics that define democratic societies and ensuring active participation, education can cultivate a sense of commitment that extends beyond the classroom, contributing to a more engaged learning community.

Freedom

Perhaps the most important aspect of shifting to a democratic education system is the opportunity for students to exercise freedom. Freedom is, however a very convoluted concept, so it is important to understand what is meant by the term. Referencing Dewey, Raywid (1987) constructs freedom in schools “not [as] a matter of mere removal of restraints,” but instead as “ways to help the child increase [their] control over [themself] and [their] environment” (p. 487). In this sense, freedom does not mean letting students have free reign over everything that happens in the classroom —indeed, this would certainly lead to a lack of structure. Rather, freedom involves empowering them with the skills, knowledge, and responsibility necessary to make meaningful and informed choices. I think Alexandra K. Trenfor’s words are incredibly fitting here: "The best teachers are those who show you where to look, but don't tell you what to see.” Graham’s (2018) insights on guidance and autonomy run parallel to this thought. He claims that educators can promote freedom by offering students the ability to make decisions, such as picking from various reading materials or project options, and by creating spaces where they can openly share their perspectives and personal experiences.